Yske, daughter of the legendary warrior priestess Hessa, has dedicated her life to medicine and pacifism in service to Aita, the Great Healer.

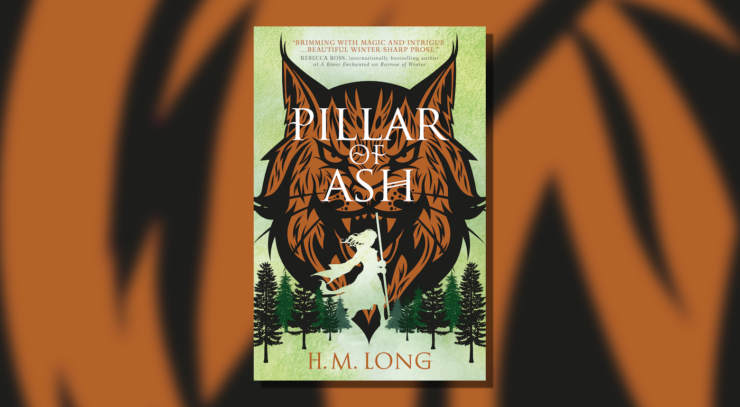

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Pillar of Ash, the fourth and final book in H.M. Long’s Hall of Smoke epic fantasy series—out from Titan Books on January 16th.

Yske, daughter of the legendary warrior priestess Hessa, has dedicated her life to medicine and pacifism in service to Aita, the Great Healer. When her twin brother Berin, hungry for glory, gathers a party to investigate rumours of strange sightings in the Unmade—shadows in the darkness at the end of the world—Yske joins the mission, to keep him safe.

Their journey east takes them through primal forests, walking paths last trod when gods were at war and ancient, powerful beasts were defeated and bound. And the closer they get to the Unmade, the more strange and terrible things haunt them from the shadows, corruptions in nature and monstrous creatures of moss and bone.

Earning the respect of Berin and his warriors, Yske must forge a place for mercy and healing in a world of violence and sacrifice. She must survive murderous ambushes and brutal sieges and take her place at the centre of the oldest war of all.

Thrust into a desperate conflict of survival, Yske and Berin will wage the final war with the gods—in the shadow of a vast and ancient tree, the fate of creation is about to be decided.

The knife was smooth and cool to the touch: simple, plain, but terribly sharp. Light glinted off the blade as my mother settled my small fingers around the hilt. When I tried to let go, her callused hand held mine in place.

“Do not come out until I call for you,” she told me.

The wind picked up around us, heady with pending rain and violence. My gaze flicked past the arc of the shield on my mother’s back, through the swaying trees and rustling undergrowth to the empty trail.

“Hessa!” a voice roared through the trees.

My mother clamped a hand over my mouth before I could whimper in fear. She hovered, perfectly still between the boughs of pale green needles.

Buy the Book

Pillar of Ash

They were looking for my mother. Whoever was out there in the forest was looking for her, and there was no gentleness, no forgiveness in their voice.

“Those are the Iskiri,” my mother murmured, low and warning. “If they catch you, if they realize you’re my daughter, they will kill you. Tell them you’re Algatt, and pretend not to know me, even if I’m hurt. No matter what they do. Do you understand? Yske?”

I couldn’t nod with her hand so firmly over my mouth, but I blinked a frantic, fluttering acknowledgment. Slowly, she let me go. I lifted the knife, clutching it with all the strength of my terror, and nodded.

Noting my clumsy grip, she grimaced and touched my cheek with a gentle hand. “I will teach you how to use that when we get home. Stay here. Stay silent.”

I nodded again and she vanished into the forest.

Quiet settled around me. Nothing moved in the fir grove save the wind tugging the boughs and a few stray needles falling into my hair. Tentatively, I shifted to all fours and stared in the direction my mother had gone, but otherwise I did not move. I would be like a rabbit in the garden, I told myself, holding so still the dogs couldn’t see me.

I heard a scream. It was a shocked sound, full of pain, but it belonged to a man. I bit my bottom lip and screwed my eyes shut.

Running. An outbreak of shouts and a husky, growling war-cry, fringed with bloodlust and ending in a cracking canine yip. My eyes flashed open as footsteps flitted past my fir grove, light and leaping. Their owner howled, then loosed a manic laugh.

I realized I was shaking, and that made the tremors worse. I sat down hard, dropped the knife, and covered my face. I prayed silently, a clumsy imitation of my mother’s prayers—one prayer to Thvynder, god of my people, and another to Aita, the Great Healer, who made all things whole and well. When my prayers ran out I held myself tightly, wishing I was anywhere but here, and at the same time longing to be at my mother’s side. At least if I could see her, I’d know she was alive.

It began to rain, hard and swift and cold. The trees swayed and the sky darkened, leaving me in a bewitching twilight. I squinted against the droplets and bowed my head, my misery and fear reaching a breaking point.

I didn’t make a conscious decision to leave the grove, but my next clear memory was of hovering at its edge, watching a warrior with a blood-streaked face throw my mother against a tree. Her head cracked off a root. She rolled and tried to push up onto her hands and knees, but her whole body shuddered. Her head lolled, eyes blinking, squinting. Fluttering shut. Her axe lay on the forest floor, glistening in the rain, and a long knife toppled from her fumbling hand.

The rain did nothing to wash the blood from her attacker’s face— multiple gashes bled freely, and as he snarled at my mother, I saw his teeth were filed to vicious points.

An Iskiri Devoted. I’d heard the stories many times in my eight years. Though the adults tried to protect us from the worst of those tales, other children gleefully whispered the details between themselves. Iskiri Devoted still served Eang, the Goddess of War, even though she was dead and hadn’t really been a goddess at all but a Miri—a powerful being, almost immortal.

The Iskiri Devoted reveled in killing the priests and priestesses of new gods in the most brutal, bloody, and painful ways. But my mother wasn’t just a priestess. She was the High Priestess.

She had killed Eang.

The Iskiri tore a hatchet embedded in a nearby tree and threw himself at my mother. My mother, already on the ground. My mother, who protected others, protected me. Loved me.

My fear flickered like a candle in the wind. That wind was a battering, righteous indignation, a refusal to accept the reality of the moment and the truth of what was to come. Then there was no thought in me, only rage that burst through my veins—hot, blinding and feral.

I shrieked. I threw myself from the trees and onto the Iskiri’s back. My fingers clawed his face, his throat. They pried into his eyes.

He threw me to the earth and spun on me, spitting blood and roaring like a wounded bear. I rolled right back onto my hands and knees and weathered the force of his fury.

My mother’s knife was in my hands. I darted forward and stabbed at his calf, down to the bone. The man stumbled and I went after him, still unthinking, carried on a wave of hate and the need to destroy the cause of my fear and my mother’s pain. Another stab, this one to the thigh. He tried to grab me by the hair; I dodged and hacked at his ankle.

But rage couldn’t change the fact that I was a child, and particularly small for my age. Another lunge—the Iskiri plucked me from the ground and threw me like a doll. I smashed back into the stand of firs, branches cracking and bending, tufts of needles painting blood across my skin.

I hit the ground and did not move again. I couldn’t. The anger that had fueled me sputtered with the erratic beat of my heart. All I could do was stare through tear-filled eyes as the Iskiri picked up my mother’s axe and advanced on her again.

I opened my mouth to scream, to try and save her with my tiny, torn voice. But Hessa moved. Wielding a fallen branch like a spear she staggered to her feet, smashed the axe aside and snapped the other end into the man’s face. His head cracked back and she pressed—beating him again and again in the head, face and shoulders until he collapsed, choking on blood and shattered teeth.

My mother did not stop. She kicked him onto his back and straddled him, branch braced across his throat. He clawed and beat at her, but she was impervious—she didn’t break his gaze until his hands fell limp and his fingers, creased with mud and blood, twitched on the sodden bed of needles.

Hessa unfolded slowly and stepped away from the corpse. Chest heaving, she spat blood and retrieved her axe, holding it loosely in both hands.

A new kind of dread gripped me then, twining through remnants of my ferocity and an incomprehension of what I’d done. That dread wasn’t directed toward the blood on my lips, or worry that my mother was badly injured. It wasn’t even because of the body, lying face-up in the rain. No, this new alarm came from the expression on my mother’s face—cold, remorseless, and weary.

If my rage had been a fire, hers was a deep, drowning sea.

She saw me and her expression faltered. I didn’t know if she’d seen everything I’d done, but I saw regret flicker through her eyes, the promise of a difficult truth. Then she brushed a tired hand over her face, slicking away blood and rain and black hair caked with dirt.

“Are you hurt?” she asked, composed now, her expression guarded.

I looked down at myself. I ached and was covered with cuts, but those pains were distant. “No,” I said simply.

“Then stay there. Wait for me.” She vanished into the trees again.

I stayed this time. I couldn’t have moved if I’d wanted to, for as I sat beneath the fir boughs and watched rain drip on the face of the dead Iskiri, something within me fractured.

Excerpted from Pillar of Ash, copyright © 2023 by H.M. Long.